KAMISAKA SEKKA (1866-1942)

Autumn plants and flowers

ca. 1920

Size of painting: 54 x 20 in.

Size with mount: 78 1/4 x 26 in.

Color, ink and gold on silk; original signed box and mount

Hanging scroll

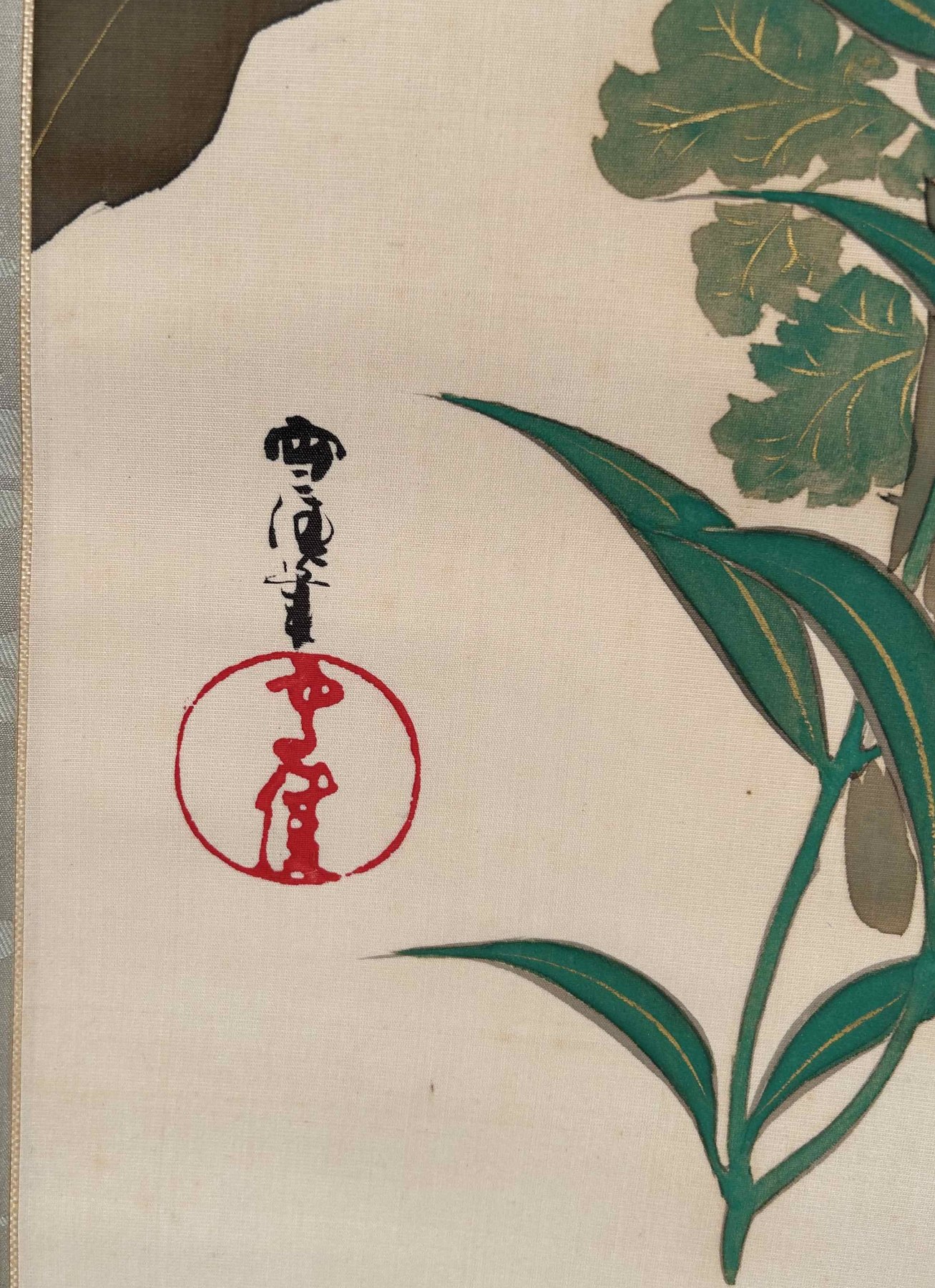

Signed: Sekka

Sealed: Sekka

Box title: Akigusa no zu; View of Autumnal Grasses

Box signed: Sekka hitsu

Price on Request

The work of Kamisaka Sekka defines Japan’s modern art movement, and this masterful painting is an exceptional example of his highly decorative late style that combines the celebrated traditions of stylized imagery and painting techniques of the Rimpa school with the bold lines of modern design.

This autumnal array of flowering plants is a subject to which the artist turned at many points in his career in a variety of media. Sekka produced other paintings of autumn foliage with similar painting techniques (for a set of four fusuma doors painted in 1918 for the Sôka-den residence of Shôren-in Temple, Kyoto, with the same plants see pp. 76-77 in Kamisaka Sekka: Rimpa Master, Pioneer of Modern Design). The gathering of seven plants includes blue bellflowers (kikyô), white chrysanthemums (kiku), mauve asters (nokongiku) red amaranthus (hageitô), green eulalia (susuki) and the central ditch reeds (ashi). Central to the composition are reed’s twisting leaves artfully executed with the extensive use of the mottled tarashikomi technique of pooling ink with green and gold. Interestingly, in 1893 Sekka named his painting group after this alluring plant, the Ashide-kai. The left screen of a pair of six-fold screens by Sekka in the collection of the Hosomi Museum, bearing the same signature and seal, also portrays a selection of these autumn plants (see Kamisaka Sekka: Inheriting the Timeless Rimpa Spirit, Hosomi Museum, Kyoto, 2021, pp. 140-41). Especially large in scale and in impeccable condition, this remarkable scroll also retains its original silk mounting and box.

Kamisaka Sekka occupies a unique position in the history of Japanese modern art. Unlike his contemporaries, his achievements were not limited to the sphere of painting, but also included designing lacquer ware, ceramics, and textiles. Born in 1866, two years before the Meiji Restoration, Sekka began his study of painting at age sixteen in the Shijô school tradition under Suzuki Zuigen (1847-1901). His first professional job was as a designer for the Kyoto Kawashima textile company, but exposure to European decorative art convinced him to change course. In 1888, at age 23, Sekka began to study Rimpa-style painting under Kishi Kôkei (1840-1922) in Tokyo. The Rimpa tradition, which became Sekka’s lifelong path, was considered a uniquely Japanese form of aesthetic expression. Despite societal pressure to look only at painting as art, he worked toward preserving the tradition of arts and crafts by successfully integrating various materials, sometimes producing mixed media works like this screen with its intricately woven textile applied to the bottom half of the composition.

Especially large in scale and in impeccable condition, this remarkable scroll also retains its original silk mounting and box.

In 1901, Sekka went to Europe to see the Paris International Exposition and took the opportunity to visit numerous European museums. Upon his return to Japan, he accepted a teaching post at the Kyoto Municipal School of Arts and Crafts, began a long career in judging both fine and decorative arts at numerous competitions in Japan and later in France. Soon thereafter, Sekka organized two groups of Kyoto based artists that later merged into the Katsumikai, which changed its name many times but survived in one form or another until 1939. The mission of this group was to study the applied arts, sponsor public semiannual exhibitions, conduct seminars, publish magazines, and so on. In this way, Sekka became the unifying and driving force in the revitalization of the decorative arts of Kyoto and a leader in Japan’s modern art movement.

In addition, he personally contributed to the re-evaluation of the prominent artists in his beloved Rimpa tradition, by first establishing the Kôetsukai, which threw new light on the now celebrated artist Hon’ami Kôetsu (1558-1637), also a gifted calligrapher, designer, and producer, and then through events honoring Ogata Kôrin (1658-1716). In his own work, he paid artistic homage to their genius, through his effective use of techniques, subject matter, and style all initially pioneered by these masters.

Contact us for price, references, and more information about the artist at director@mirviss.com